Words by Will Allstetter for Hypeart

At the end of January, Transmediale returned to Berlin for its 39th edition. The art and digital culture festival wove through the city and took root in an eclectic mix of venues, ranging from Berghain to the Canadian Embassy. Navigating the programming required transferring between trams, subways, buses and cars, as well as shuffling on frozen-over sidewalks.

Though partly a logistical byproduct, the geographical network the festival embedded into the city was cannily on target for its theme: “By the Mango Belt & Tamarind Road.” In their thematic compass, curators Neema Githere and Juan Pablo García Sossa write, “the festival is reimagined as a living recursive carrier net — a hammock of relational technologies in practice that stretch across latitudes, rhythms and systems.” The title is a nod to China’s “One Belt One Road,” an economic initiative that, in the curators’ words, “often frames itself as an alternative to development yet perpetuates dependency structures.”

Positioned this way, the festival acknowledges that networks, especially the digital ones, are tricky structures. They are both ephemerally digital and infrastructurally physical. Ideologically, their utopian collective ideals frequently bend towards extraction and exploitation. In “Infrastructure Anxiety” — as GIFs of pop-culture iconography, including Paris Hilton, Minecraft and Serial Experiments Lain looped — Cade Diehm dubbed the uncanny marriage between the digital and the physical the “para-real.” Cybernetics’ “psychopathic pursuit to preserve data” seeps into our physical world and creates blurry para-real effects. Diehm points to symptoms such as the anxious paranoia permeating online interaction and the ex-NSA chief’s admission: “we kill people based on metadata.”

Computation, the participants reminded us, is not solely the software and hardware we’ve become accustomed to.

That understanding does not mean, however, that Transmediale’s artists have given up on the net’s potential. Instead, the cohort converged on Berlin (and abroad, with satellite “netting groups” in Thailand, Papua New Guinea and the Swahili Coast) to bootstrap their own. As per the curators, the festival sought to explore not just how to diversify and improve existing models, but looked to the “tropics and beyond” for completely new “recipes and architectures of relation that outlive standardisation and universality.”

In that vein, computation, the participants reminded us, is not solely the software and hardware we’ve become accustomed to. In “Kolams” (which you can try online), Aarati Akkapeddi adapted the Tamil and Telugu art form of drawing algorithmically complex designs using rice flour and turmeric. As an act of mourning for her grandmother who practiced the art form, Akkapeddi created a computer program for encoding text into these designs. Computation is not all silicon and wires, sometimes it’s flour and spices.

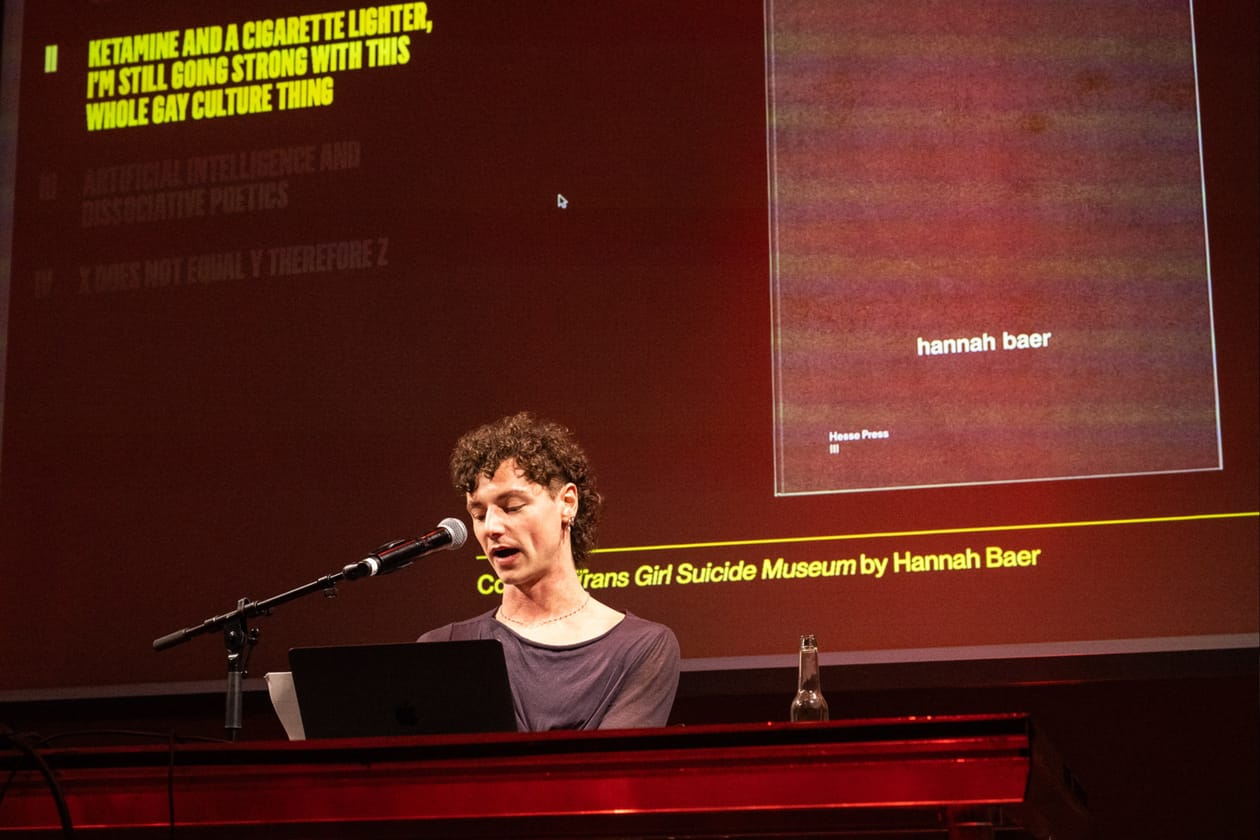

Introducing QT.Bot, Lucas LaRochelle provided a framework for conceptualizing the week’s web of participants: “in difference, together.” QT.Bot is an artificial intelligence trained on data from LaRochelle’s project, “Queering The Map,” a website that allows users to share geotagged queer experiences. “Queering The Map” is not your typical database. It is intentionally anonymous and opaque. The entries float on their own, the text encapsulating only the individual moment. LaRochelle throttles the model before it gets too good at mimicry. Instead, they create a “dissociative” representation that often hallucinates, contradicts itself and outputs pseudo-nonsense, with lines such as “four 17-foot tall trans women in yellow jumpsuits hitched rides outside our house at 8AM in Midtownhattan.” Pushing against the summary view of the network and advocating for a plurality, they asked the viewer to be comfortable with “multiple realities.” LaRochelle’s voice was distorted beyond recognition to embody an inhuman force channeling the network, as it narrated the LLM’s output. Although, if you listen closely, their Canadian accent poked through.

Without judgement, festival-goers were encouraged to reframe their concepts: not as objects from which to sap any use-value, but nodes in a weaving lineage of thought.

Later, Tsige Tafesse led the meditative “Embodied Citation.” Eyes closed, the audience traced the genealogy of a concept of their choice. The network, in this instance, was temporal and interpersonal. Facing the crowd, she prompted us to consider how our concepts (I chose an adage passed down from my mom) were shaped over time and communication. As we imagined, she offered provocations on how “grammars of power” manipulated these concepts. Without judgement, festival-goers were encouraged to reframe their concepts: not as objects from which to sap any use-value, but nodes in a weaving lineage of thought.

Beyond performance, the festival hosted installation pieces. “LAWALAWA,” a woven Isola Tong basket, sat above the entrance of the Silent Green, the festival’s homebase. Referencing its holding abilities, the meshwork was a metaphor for the space it introduced: a supportive environment to pause, consider and regenerate. Once inside, Hoo Fan Chon’s “Tilapia Shrine” tackled system thinking from another angle. On a bookshelf in the back of a dark room, Hoo positioned a glowing fishtank. Lighting up the water, an LED matrix panel frantically flashed graphics and text reading “Tilapia Shrine (Closed System for Care and Circulation)” as toy fish aimlessly bobbed around. For Hoo, Tilapia is a species that sits at the intersection of many webs: economic impact, environmental contributions, and Malaysian-Chinese cultural symbolism. With brash lighting and artificial fish, a shrine like this is built to honor the nuanced cultural webs in which we currently swim, accepting a sustainable future to be something less pastoral than imagined. Across the city, in the Dong Xuan Center, a similar LED sign joined the network. Above a stall in the 500-acre Asian wholesale center, a ticker tape poem by Ben Okri illuminated goods from across the world, reading “In the beginning there was a river. The river became a road and the road branched out to the whole world. And because the road was once a river it was always hungry.”

In globalized networks like these, the viewer not only participates in, but becomes a part of the network, internalizing it.

In all the speculation, however, the festival did not lose sight of economic pragmatics. In “Current·Seas,” artists shared how their practices were supported by alternative economic structures. Gladys Kalichini explained how Chilimbas — a Zambian communal credit-based savings system — facilitated the execution of her work. Kalichini did not present Chilimbas as a utopian alternative to existing financial structures, because “banks use the same logic.” Yet, with their organic and trust-based communal networks, by borrowing from the Chilimbas, she not only had access to funds, but leveraged by their investment, she was able to enlist community members in the artistic labor.

Commerce was even happening within the festival itself: On opening night, I deposited six euros into Kathleen Bomani’s “Deera World” in exchange for a garment. A group assembled, curious what the compact reflective packaging in the vending machine contained. Out came a wonderfully fragrant and colorful Deera, a Swahili feminine garment. Bomani explains that “the garment circulates through an informal economy of relationships. Nearly half of all Deeras are gifted, borrowed, drifting between households rather than purchased.” She uses this context to highlight “non-extractive network of femme solidarity, protection and shared resources.” A product of circulation, however, the fabric is also a reminder of the network’s unwieldy sprawl. Intended as a “potent technology of Swahili femme subversion,” the object’s semiotic weight is much less obvious once purchased by a white American man in Berlin.

In globalized networks like these, the viewer not only participates in, but becomes a part of the network, internalizing it. The content I consume and the labor I contribute circulate in the economic, social and digital nets the festival concerned itself with. In acknowledgment of that, the festival hosted some edible pieces as well. For “Liquid Assets,” Gosia Lehmann, Sarah Friend and Arkadiy Kukarkin broke down US cash into syrup and made cocktails for attendees. Dressed in jumpsuits, the trio served concoctions in beakers, with names like “Legal Tender” and “Pyramid Scheme,” each with their own rules for earning and consuming them.

Across the web of art, performance and workshops presented at Transmediale no singular conclusion emerged. The lines between nodes did not point to one central piece of information. Which, in many ways, was the point. Extractive and finite views of networks look to simplify the network to a valuable deliverable. The webs, nets and holding structures presented, on the other hand, happily accepted the plurality of their communion.